Guest Column: The Evolutionary Transformation of Supply Chains

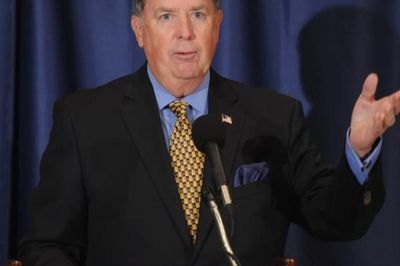

Kevin Smith was moderator for this year's CSCMP State of Logistics Report presentation in Washington, D.C.

“It is not the strongest…that survives, nor the most intelligent that survives. It is the one that is most adaptable to change.”

-- Charles Darwin

Much has changed in the way supply chains operate over the last half century. In fact, the term “supply chain” didn’t even exist 50 years ago. End–to-end supply chains have only been a conceptual reality for about 20 years.

In the 1960s people were apt to talk about warehouses, trucks and railcars as vaguely related, but unconnected. Most products were “dead-piled”, or hand-loaded, into trucks and railcars for shipment. Palletized shipping was not fully in vogue. Inventory management meant counting what you had, not projecting what you might need.

The people involved in these activities were consigned to the backroom: the necessary evil last step of the sales process. And, these activities required a lot of people in very labor intensive processes that included hand typed bills of lading and hand calculated weights for waybills.

The advent of computers (yes, it wasn’t that long ago that computers did not exist!) streamlined the paperwork. Computers also paved the way for sophisticated planning and forecasting that attempts to match production of inventory to expected demand.

Warehouses that simply served as places to pile stuff up gave way to distribution centers that create coordinated flow processes for more JIT (just-in-time) shipping. Palletized shipping, slip sheets and clamp equipment sped up the storage and retrieval processes.

RORO, or roll-on/roll off equipment, allows entire containers of product to move efficiently as a unit. And, finally, automation is beginning to replace people in many receiving, storage, retrieval and selection processes. Large grocery distributors are able to machine select, and palletize entire truckloads of mixed products in perfectly square, seven-foot high pallets without human hands.

These changes occurred over a protracted period of time. Some so slow that we hardly noticed. And, it turns out that supply chains that adapt to these changes best are probably the ones that will survive while others will perish in bankruptcy or acquisition.

There are some obvious reasons to adapt. Inventory is too expensive and the risk of obsolescence too great to not engage in predictive analytics. Companies who do not match supply to projected demand do not fare well economically and when current artificially low interest rates begin to rise again to historically normal levels this will become even more pronounced.

A bigger issue arises from a less-visible challenge. The population is shrinking and we are going to run out of people to do the work inside of supply chains. I know it is hard to believe. In a world that currently has over seven billion people, and growing to eight billion, how can we run out of labor?

The answer is simple and scary. The population continues to grow primarily in under-developed Africa and parts of Asia. Europe is already in population decline. In fact, Germany imports over a million workers from eastern European countries each year just to keep pace with labor needs.

By 2025, North American populations will be in significant decline, and the talent sourcing issues of today will pale by comparison. We will simply not be able to attract a sufficient number of people to do the jobs we need done.

Young people will be able to choose whether they work at a boring, air-conditioned computer job, or work in a potentially uncomfortable distribution center. It will not be a tough decision, and it will not work in favor of supply chains operators.

So, supply chains must work diligently to discover and adopt new methods, processes and innovations that displace mundane work, in order to free up talent to do the things that humans must continue to do.

For example, automating receiving, put-away and retrieval activities can free up an incredible amount of workforce talent to handle more critical processes.

Likewise, finding supply chain partners and third-party operators who are early adopters of innovative practices may provide a company advantages over their competition because their people will be focused on the future, not fire fighting today’s problems.

Changes happen slowly, but supply chains cannot wait to adopt lots of changes all at once. Organizations must be vigilant in identifying transformational changes that will allow them to outpace competition and grow their businesses without stumbling.

They must then find ways to continually adopt and adapt changes to ensure that they remain at the front of the evolutionary line.

Charles Darwin described the evolutionary process as “natural selection” or the survival of the fittest. But he was adamant that it is not necessarily the strongest or the most intelligent that makes the cut. The survivors are those that are most adaptable to change. The same is true for supply chains.

By Kevin F. Smith

Kevin Smith (moderator for this year’s presentation of the Council of Supply Chain Management ProfessionalsState of Logistics Report, presented by Penske Logistics) is the 2015-2016 CSCMP board of directors chair. He is also president & CEO Sustainable Supply Chain Consulting.

Editor's Note: Mr. Smith's views are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of Penske.